Previously Published in The Messenger

It’s rare that a third-party candidate has the momentum that Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., does. It’s also rare to see the two major parties visibly shaken by the presence of a third-party contender on the ticket.

The last “strong” display of a third-party presidential campaign was Ralph Nader’s 2000 run on the Green ticket, in which he was described as a “spoiler” for Al Gore (D-TN) against George Bush (R-TX). This mainly came down to the nightmare scenario in Florida that stymied the election results for nearly a month, but we caution our readers to also remember the razor-thin margins in New Mexico, Iowa, Oregon, and Wisconsin, followed by close margins in Maine, Minnesota, Pennsylvania, Washington, and Vermont. Several of these states have long eclipsed the perennial electoral scorecard – although we’re optimistic some might return to the competitive board this year. Our point in saying this is that Nader’s paltry 2.74% of the popular vote could have been a spoiler for Gore, but it theoretically could have precluded Bush from a much larger Electoral College win.

Before Nader, the only strong third-party candidacy we can remember is Ross Perot’s (I-TX) bids in 1992 and 1996, the former of which he is credited for spoiling for George H.W. Bush (R-TX). Perot took nearly 19% of the nationwide vote but failed to carry a single state.

In recent years, we’ve seen some third-party models who leave much to be desired. Gary Johsnon’s (L-NM) Libertarian candidacy in 2016 still makes people laugh with his “what is Aleppo?” gaffe and his near-instantaneous indignance at answering any questions of substance, usually dismissing them with his claims that he helped legalize marijuana in New Mexico during his time as a Republican governor.

This year, the Libertarians really did it this time with Chase Oliver, a former Democrat who you would still think is a firebrand progressive Democrat by the looks of him. It’s funny how the party of intrinsic American political philosophy is dominated by leaders who make their platform about marijuana and hookers.

The Greens usually don’t have much to say for themselves either. 2016 presented pathological climate rioter Jill Stein, who’s running another campaign for the White House this year.

Then there’s Cornel West, an age-old political “philosopher” who’s made his money talking about race and socialism.

In short, RFK is, according to the general public, a breath of fresh air in the realm of third-party candidacies. People are clearly turning out in droves to get him on the ballot, as his campaigns returns petitions with signatures more than tripling the required amount in some states.

New York was no exception. In a state that required him to obtain 45,000 signatures, he turned in almost 136,000.

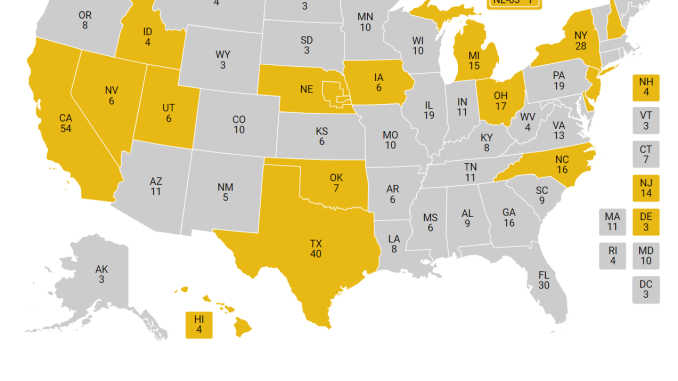

He’s now on the ballot in sixteen states worth 229 electoral votes. At this point, it begs the question: how much of a chance does he really have?

The first part of the equation you could argue helps him is that a recent Gallup study found that 43% of Americans are registered as Independent, a new high in modern history. While Republicans maintain a slight edge in registration over Democrats, they’re effectively tied at 27% apiece.

The problem is how this translates into Electoral College math. Sure, Kennedy has secured ballot access in the biggest prizes: California, Texas, and New York. We’re sure Florida isn’t far behind. Florida would give him an additional thirty Electoral College votes, with just eleven more to make it to the magic number of 270. At this point, ballot access doesn’t seem to be a concern for RFK. He’ll likely get on in all fifty states. His problem is in convincing enough voters in a hyper-partisan era to have second thoughts at the ballot box, preferably for him.

RFK would likely want to start in the western half of the country, where Independents are a dime a dozen and the states have histories literally founded on third-party success and fusion tickets towards the end of the 1800s. Alaska has the highest concentration, with Colorado, Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon, Washington, New Mexico, Utah, North Dakota, and South Dakota as viable alternatives.

If RFK were to somehow win all of those states in November, he would only receive sixty-one electoral votes.

The eastern half of the country is much more polarized, but there’s still some options for him. Vermont, Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and New Jersey have some good blocs of Independent voters. For the sake of the argument, we’ll give him Connecticut and Rhode Island as well, as New England tends to vote rather monolithically.

Together, with the aforementioned western states, he’s only at 108 electoral votes. At that point, we think enough crossover support would have occurred to send the election to the House, as neither Biden nor Trump would likely have hit 270.

Since we have the benefit of this just being hypothetical, we’re not inclined to believe this is a likely scenario. However, it’s one that’s worth exploring as we navigate these relatively uncharted waters together.

At the end of the day, RFK still faces a near-insurmountable task: convincing the highly polarized electorate to ditch party loyalties and try something new in a truly novel hybrid candidate. In an era where split-ticket voting is at an all-time low, we don’t think this is quite set to happen. As recent polling indicates Trump could either break even among Independents, or even win them outright, both he and RFK are shaping up to take away a portion of the electorate that has been crucial to Democrats for years.